Biography

Biographical Note

Arturo Puliti was born as a “Florentine painter” from the critic Raffaele De Grada and L’Indiano Art Gallery in Florence owned by Piero Santi and Paolo Marini. He studied at the Arts Institute in Pietrasanta (Lucca).

In the early years of the second post-ward period he worked as an ads graphic designer, as well as a painter. In Rome, he contributed to the humorous weekly magazine Elefante, a short-lived magazine of the dairy newspaper Il Tempo. This job, though, helped Puliti to meet personalities such as Maccari, Cagli, Mirko and Nantas Salvalaggio.

In order to be part of the most lively painting schools of the time, he lived in Turin from 1948 to 1949, in Zurich and San Gallo (Switzerland) from 1949 to 1953, still retaining his living place in Rome. In that period he started his “quarry” cycle, one of the most prolific outcomes of his art.

In 1957 he spent a year in Milan where he made friends with Achille Funi, B. Cassinari, R. Birolli, and some painters of the Bergamini Group. In the summer of the same year he made friends with Roberto Longhi who would introduce him to the “Caffè del Quarto Platano” in Forte dei Marmi, and met Carlo Bo, De Robertis, the De Gradas (the painter, the critic and Magda, the mother – a poet), the writer E. Pea, the poets Luzi, Parronchi, Montale, Gatto, Ungaretti, Orelli Bertolucci, the painters Carrà, Soffici, Morandi and many Others, and Oreste Macri, the famous Spanish Literature scholar. From 1959 to 1963 Puliti spent some time in Paris, first in Montpanasse, then in Montmartre. From 1965 he lived and worked in Florence and in Versilia. The great flood destroyed his studio in via Varlungo in Florence which he shared with his friend the sculptor Ugo Guidi and he obtained special funds from the Opera Theater of Chicago. He made Exhibitions in Munich (several times), Lindaou, Wurzburg (Germany), Zurich, S. Gallo (Switzerland), Paris, and in the main italian cities.

In 1968 he was awarded the first Prize for the “New values of Young Italian painting”, among twenty italian avant-garde artists who had been selected by Marco valsecchi, Raffaele De Grada, Piero Santi and Ernesto Treccani. In 1970 the Art Gallery L’Indiano (Florence) published his first monograph volume with contributions by Valsecchi and Piero Santi (in that period, he met Giorgio La Pira and Pero Bargellini at L’Indiano). Over the years, the same gallery published other volumes which won the appreciation of many critics (among them, Florentine Spaces, with contributions by Raffaele De Grada).

He held the “Nude” chair at the Academy of Fine Arts of Florence, as well as the “landscape” chair. Such experience helped him build a profitable relationship with his students and allowed him to meditate upon technique which, as someone said, “needs be learnt only to be completely forgotten about when painting begins”.

In 1975 Puliti was one of the ten artists the Regional Council of Tuscany appointed to produce a set of engravings which were donated to the “Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe” of the Uffizi gallery. In 1976 he was awarded the first Prize of Painting by the Lorenzo Viani Foundation of Viareggio (with subsequent exhibition).

Puliti is also one of the three founders of the “Premio Satira Politica” of Forte dei Marmi, whose logo, a stinging bee, was created by Puliti himself. Even though he was in touch with the greatest maestri of the twentieth century, and even if he has had the support of critics such as Roberto Longhi, Raffaele De Grada, Marco Valsecchi, Piero Santi, Bruno Corà and M. Fagiolo Dell’Arco, Puliti has Always kept himself to himself, pursuing his own idea of painting and refining a peculiar symbolical Language and an unrivalled chromatic syntax which put him far beyond any school or tendency. He died in 2011.

Taken from a text by Fabio Norcini

Critics that wrote about him:

Marco Valsecchi, Mario Luzi, Roberto Longhi, Raffaele De Grada, Lara Vinca Masini, Mario Portalupi, Umberto Baldini, Mario Lepore, Piero Santi, Franco Miele, Pier Francesco Listri, Raffaele Monti, Vanni Bramanti, Elda Fezzi, Renzo Federigi, Tommaso Paloscia, Dario Miccacchi, Maurizio Chierici, Corrado Marsan, P.M. Bode, Luigi Baldacci, C. Popovic, Luciano Luisi, Pier carlo Santini, A.B. Del Guercio, Elio Mercuri, Emilio Paoli, Antonella Serafini, Roberto Coppini, Gianni Pozzi, Onofrio Lopez, Mario Novi, Michelangelo Masciotta, Magda de Grada, Rolando Bellini, Fabio Norcini, Giuseppe Sprovieri, G. Biazzi Vergani, Carlo Ripa di Meana, Marisa Vescovo, Eugenio Miccini, Bruno Corà, Maurizio Fagiolo Dell’Arco, Enrico Crispoldi.

Critics

Critic Notes

- (Italiano)

L'esperienza conoscitiva da poco compiuta (almeno per un primo ampio approccio) dell'opera di Fernando Melani, l'artista pistoiese scomparso nell'85, ma che tanto ancora, credo, farà parlare di sé, mi ha indotto recentemente ad alcune riflessioni di fondo sull'atteggiamento di quegli artisti che, o per scelta individuale o per ragioni diverse e indipendenti dalla loro volontà, sono "restati in disparte" dal più vasto riconoscimento che prima o poi incorona gli "insiders" o i più assidui al dibattito, allo scontro o alla quotidiana frequentazione dei mass media.

E quella di Arturo Puliti, appunto, sembra una vicenda così talmente vissuta solo "dentro" la pittura che deve avergli lasciato poco margine per ogni altro diversivo. Sta di fatto che il suo, se ci si attiene alle opere che la mostra romana di Sprovieri propone in lettura - quella pittura concepita ed eseguita interamente nella decade degli anni '50 - è episodio di lavoro assai puro e fortemente determinato, esteticamente pervaso da un intimo furore - è il caso di dire - escavatorio , nonché analitico, che riflette alcune delle "costanti" attorno a cui si sono espresse le lezioni più alte della pittura di questo secolo (da Cezanne a Morandi,, fino a Castellani): la "ripetizione", quale atto evocativo che considera virtualmente un unico esemplare modello su cui tornare ad esprimersi producendo l'infinita differenza del "medesimo" è forse la scoperta cezanniana più feconda di implicazioni filosofiche giacchè costringe ad un "vis-à-vis" cruciale l'infinito movimento e mutamento del mondo con la mobile coscienza dell'artista che lo osserva e ne ricrea l'armonia.

E sia nel caso che la natura considerata dal pittore gli sia apparsa "en plein air" (Cezanne), o "morta" (Morandi) o nell'invisibile pulsazione temporale (Castellani), la luce p stata l'elemento essenziale a rivelarne l'infinita differenza di stato e qualità.

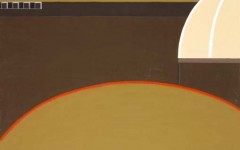

Le "cave" versiliesi e garfagnine davanti a cui gli occhi di Puliti hanno sostato e meditato, di giorno o al crepuscolo o in piena notte, è pur vero che altro non offrono che "pretesto" al teorema, la cui formulazione è rivendicata da Longhi e dimostrata da questo artista: "L'astratto esiste in natura".

Così la cava "Ceragiola" (1953) o quella di marmo del "Piastraio" (1955) o la "Scaglia" (1959), dipinte da Puliti con l'assiduità di un orante, invocano la "Sainte Victoire" come visione antenata e ne mostrano, nella declinazione gestuale macroscopica ed endoscopica, la più intima essenza: molecole di colore accanto a molecole di colore. Dietro quei pigmenti che non disdegnano le contaminazioni, stesi a spatolate, dati a strattoni, quasi ad inseguire e suscitare la durezza della materia che pur vogliono evocare, vi è sempre una mirabile, organica invisibile costruzione.

Si osservi ad esempio il piccolo olio su cartone "Cava in Versilia" (1956), ove una atmosfera di rosa vagante ovunque, stemperato dal bianco, a tratti coperto dal verde o dal grigio e con al centro una campitura ocra appena squadrata, emblematizza la ripartizione volumetrica più che per piani, dell'intero spazio pittorico. Alle accennate segmentazioni di differente stesura cromatica (i tagli dei blocchi di pietra) per lo più marcanti la verticalità del piccolo dipinto, fa da contrappunto organico l'andamento connettivo di una traccia che sale leggermente inclinata a zig-zag (una carreggiata della cava?) entro tutto il tessuto della composizione pittorica.

Ma quell'opera è vessillo attitudinale di tutte le altre relative al periodo in mostra, cioè quello compreso tra il '53 e il '59. Nel ciclo delle cave, infatti, Puliti dell'astrazione ha praticato sia la valenza di derivazione cezanniana, cioè analitica, come pure la regola neoplastica che, dopo tutto, la natura delle cave suggerisce.

Cavità e sporgenze, depressioni e altezze che compongono il paesaggio di antitesi volumetriche e spaziali che Puliti ha metabolizzato in differenza cromatica e spazio pittorico.

E non contraddicono quest'attitudine nemmeno gli olii su tela "Calcare e Vegetazione - Monte Forato-notturno" (1956) e "Cava di marmo al crepuscolo" (1959) o "Cava di marmo in Versilia. Vista notturna" (1959), se si considera che le tenebre, come invisibile amalgama intessuta di colore, tendono a cancellare le scansioni delle cubature e dei tagli per spandersi quasi come sinonimo dell'impasto pittorico entro tutta la superficie del quadro.

Diurne o notturne, le visioni di quelle cave che Puliti restituisce sulla tela rivelano che, ben al di là di essere stati luoghi reali visitati dal suo sguardo, esse furono identificazioni di un habitat interiormente conformato, cioè spazio archetipico costruito e decostruito secondo l'immaginario, dunque opera del linguaggio.

E si deve pur dire che negli anni '50 l'invenzione di questo "monotema" delle cave declinato da Puliti, accanto a quello non meno efficace di una pittura segnica praticata in modo ispirato da pochi altri, appare come il "mantra" di un credente nell'atto di celebrare il laico irrinunciabile rito quotidiano della pittura. Montagna la cui escavazione non ha fine.

- (Italiano)

Ho ragione di ritenere che in Arte si stabiliscono atmosfere, come risultato di sensibilità creative generalizzate.

E' quanto ci consente di ascrivere ad un tempo o ad un luogo opere diversamente inclassificabili.

Voglio essere più chiaro: si è potuto dipingere "alla raffaellesca" da chi niente aveva a che fare con Raffaello e nemmeno ne conosceva le opere; Rembrandt impronta di sé un'epoca - senza che vi siano mezzi di conoscenza in grado di portare le sue opere in paesi lontani, dove pur si dipinge a suo modo.

Questo per dire che l'originalità di un artista moderno quale è Arturo Puliti, non è per nulla offuscata dalla possibilità di vedere nella sua opera i riflessi delle ricerche più avanzate della produzione contemporanea.

Ci viene di fare i grandi nomi di Klee, Mondrian, Kandinskij e per certi versi anche di Picasso, ma per dire che egli regge benissimo la vicinanza di questi grandi. Non per trovare analogie, e tanto meno fissare imitazioni.

Arturo Puliti in uno sviluppo costante della propria creazione ha potuto fare suo quanto più caratteristico è nello sviluppo dell'arte dei tempi nostri, ha assimilato tutte le ricerche di sensibilità pur rimanendo indiscutibilmente padrone del suo io dei suoi mezzi di espressione e se fosse nato in un ambiente più libero e meno ristretto di quello italiano, poco ci mancherebbe che fosse considerato un caposcuola. [1979]

"Dawn, how difficult is it for you to rise"

Notes for Mario Luzi and Arturo Puliti

A Meeting in the name of Simone

by Rolando Bellini

It was only yesterday that, in a parlour of the Central National Library of Florence, I attended a long speech, along with Paolo Marini and Arturo Puliti, as well as many other of Luzi's friends. Indeed, is it there that the poet settled his meeting with us and it is there that he recited his strophes, read his proses and we, silent and ecstatic, listened to him, being moved, until sunset.

Piero Santi was ideally sitting by my side. Meanwhile, mario Luzi was telling us about his life's link, about his wait as a poet, and his talking his leave of it and he was explaining about his soul's motions, about the intimate link between poetry and life. The poet says that poetry, "the entire poetry is a creature, not a creation. It is thus object of creation...".

Silentium

I see the hand of the painter, who is sitting on my left (I'm talking about Arturo), contractiong and then pointing out a curve, a poetic figure in the air. His creature: indeed Arturo and Mario are both moved for the same wait; through their own personal returns, they have daydreamed of Simone's unthinkable return to his country home, tired of Avignone, eager for sheltering in his sweet Siena: from Paris to Florence, for Puliti; from those places where the poet has nourished himself through the enchantments of Florence, for Luzi, ideally marching from Genoa with Simone towards Florence, the town that the "Luzi" 's Simone Martini refuses to visit - the instrument of torture ready to tear any flesh to shreds, as it is represented by Puliti, today, as it is recited by Luzi's verses, yesterday - going towards his land, his Siena, which "looks at me" (writes Luzi) transferred into Puliti's today's geometries.

So that the literary and pictorial finction, the meeting between the two artists of today, becomes reality through the imaginary last periplus of the ancient maestro - a Simone Martini hanging on from his halo, in the mornng light which comes from his painting.

I believe that the confession of everyday's personal and absolutely poetic life of Mario Luzi be valid for both of them, especially when he seems to say: "I'm living the present as a hostage of the past".

And in the meantime, they both feel the rough fervor which is thirst for running life and for that passion which feels Paolo Marini: they both collide with the myth and with the reality offered by these Streets fellows of theirs; in the same way do they hurt my inattentive and incoherent look, as if it were the look of the art-historian, who assumes to be able to recite Paolo Valeri's creed, without falling into the chronicle's mysteries; they then make my eyes burn, by dazzling them with their dawn.

And yet them too, and even the painter Arturo Puliti, as well as the poet Mario Luzi, seem to recite softly, everyone in his own way, the latter's wonderful verses: "Dawn, how difficult is it for you to rise!".

May 10th 2000

- (Italiano)

Le chiare, lievi, assorte geometrie che Arturo Puliti dispone nei suoi spazi nitidi, e variano o ritornano da quadro a quadro spostate come le luci e le ombre di una meridiana. E' un ritmo, è una partitura che ci sono diventati familiari, tanto più che toccano una rispondenza assai più che visuale.

Ma a ogni nuova esposizione il discretissimo rigoroso amico rinverdisce il primo stupore di quel linguaggio tutto in chiaro, illuminato da una sorta di fieresca sublimità mentale: eppure sospeso su un secolare misterioso retropensiero dove rivive tutto il giro e l'alternanza delle epifanie e delle disperazioni.

For more than fifty years, Forte dei Marmi has been the home of artists who are renowned throughout Europe. Forte dei Marmi also gave shelter to local painters and sculptors such as Ugo Guidi and Arturo Puliti, two artists with stronger personalities and who have gone beyond any limitation of schools.

The contacts Puliti had with Florence and the group gathering around L'Indiano Art Gallery are such that by now Puliti can be considered a thorough Florentine artist. He is not the isolated work of an artist living in the provinces - it is a production springing directly from the research of this Florentine group which is growing far beyond the borders of Florence with the passing of time.

Puliti's art can be included in the larger school of three generations of European abstractionism. It has a logic, fut features no geometrical tendencies deriving from the far.off De Stijl. Puliti has always owned the typical fntasy of the "Eastern" school of abstractionism as started by the renowned Kandinskji.

As a matter of fact, Puliti takes so little heed of the canons of abstractionism that sometimes he feels he has to disclose his inspiration whose roots lay deep in the real world just to accept the language of abstractionism as the starting point of his research whithout being entrapped in it.

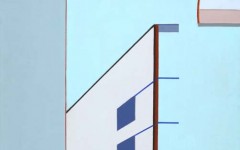

Shall we then consider this exibition - which is dedicated to the realistic aspects of his beloved Florence - as a rejection of his abstractionism conception? No, we shall not. This is no retraction, just the response to a poetical suggestion made in a language long mused upon and which derives from Florentine architecture, in particular from the Dome by Brunelleschi, the architectural symbol of a Florentine space.

The spaces of Florence - that is the topic of Puliti's exhibition. No landscape imitations, nor real landscape. It is as if Puliti wanted to teach us to look at Florence from a different angle, through a flight over its roofs and hills, beyond any limitation posed by an unrivalled architectural purity.

Puliti's paintings seem to focus upon a crossing of spaces: a plane, then a coordinated one, the another one which was unforeseen. And the reading of the painting knows no boundary, and becomes the truest spirit of such landscape vision, as if it were a mere exercise. And then viewers realise that Puliti rendered a vision of Florence seen through the eyes of a new perspective.

It is not easy to paint a landscape little known - even more difficult to paint one so well known such as Florence is. In the past days, during the conference on Ottone Rosai, we defined how deep Rosai was involved with Florence. It might as well be thought that, after Rosai, painting Florence was extremely difficult, if not impossible.

Puliti shows that the artist needs only not to get entrapped by formulae (as imitations of great "models" are likely to become) in order to be new, to convey different emotions, and to create something original. The original feature of Puliti's paintings is the way they give the Rosai-like sound, dramatic vision renewed purity. It is the same freshness one can perceive when, stepping out of a secluded place and the mechanical, corpse-like repetition of drama, one enters a morning garden where plants and trees breath in happiness. Amid so much anguished painting, amid so many asylum-like obsessions, it is a joy to the heart to have met a painter who finds again the tools and means of pure, early Renaissance disclosure. And to have shared in his afflatus.

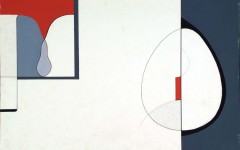

I saw some paintings by Puiti a couple of years ago at an exhibition in Marina di Massa. I was soon interested in his Conception of painting - the creation of forms and autonomous images - and in the way he makes it real, through clear-cut drawings and the use of sober colours rich in deep and refined tonality.

Puliti wants to bring to the foreground the unending varying of geometrical forms by creating modulated spaces as well as by using alternate colours on defined tones and quickly opposing chromatic values. Though he make no use of violent, furious screaming.

The colours he prefers range from cold to mental hues (grey, purple, White, brunt colours), and they do not include passionate hues (Yellow, red, orange). Tis also highlights Puliti's sobriety which allows him to reach the rhythms of the images with a more intense intellectual concentration.

Tuscan eople need not to be told that such abstractions have a right to be considered real art. Just have a look at the architectural geometries scattered throughtout Tuscany; and in Florence in particular: San Giovanni, Santa Maria Novella, Giotto's bell-tower, the side of Santa Maria del Fiore. These are not mere decorations: they are examples of an ideal harmony reflecting the order and the vividness of thought in geometrical forms.

If through such images - which are fit to project an idea of unwavering intellectual certainty against the frenzy of everyday living - Puliti feels closer to some European abstraction - from Magnelli to Arp, from Richter to Elion, to Sonia Delaunay, up to Van Doesburg and Malevitch - the artist had no need to choose Esperanto as international Language, since he was already using the clear example of the Tuscan maestri from the fourtheenth century.

I knew the Puliti of the 1952 summer in Versilia; I knew the Puliti of a few years ago; and I knew the Puliti of 1970. I was a witness to his painting, as well as to his anxiety of man of today, to the ever-increasing distancing from his birthplace, his visit to Paris, his long stays in Florence. His first landscapes were an early testimony to his vocation. The painter, though, soon realised how useless was to try and nderstand things according to naturalistic data, ad it is clear that he felt the urgency of grasping the substance and mystery of objects. It is the typical Florentine passion of reducing appearance to essence, the superstructure to the structure of things. Such passion cost much to modern Tuscan painters, probably because the first half of the twentieth century nourished other possibilities, different hopes, the deep-felt need of grasping the inmost essence of things. Rosai succeeded in doing so in a manner which is still up-to-date, as Campigli and Magnelli did. After them, though, there has only been a sour regress. Some painters where too sure of their beliefs, and, being too serious, they lacked the consuming doubt which is vital to man. They pursued the idea of an ordinary Florence, not of that unique city which cast the message for revolution, the very city of the fifteenth century which taught artists and people to be against her, as all the great maestri do.

Arturo Puliti does not frame his ideas into abstract rhythms. His painting is structured according to precise references – even though they cannot be referred to things we know. His semplification is apparent because the more it tends toward essence, the richer its resuts are. It is purification, I daresay, which does not exclude the ambiguous and contradictory complexity of reality. Under the terse texture of the colours and of the partitions of his paintings, and Beyond his meandering and straight lines, there lays the deep understanding of “things”.

Puliti’s is a strictly bare Language, the extreme expression of definitive words. No alluring in such terse mirrors: this painting “beyond informality” where the knots of the man-viper, or of the man-angel – that is, of man, who partakes in both – melt in cruel clarity. The clarity, the polished splendour (expolitum, as Catullo would say) of such paintings welcomes the inner dialectics and th fear man feels toward himself his secret, his moves, some grey acts which are anguish for the living. The invention of suchforms – overlapping, intersecting, eventually reaching the point of light and revelation – is born out of a secluded mood springing into warm judgement. It is not a search for external rhythms.

Is this, then, real avant-garde (shall we talk about it)? Digging into those cursed meanings in order to reveal their mistery and richness; being burnt by their fire – treacherous? friendly? – then burning them into new forms which are their indispensable forms, judging them in their misery and splendour by the small flame of the crisis of 1970, both poor and sublime. Beyond all this, what is the sense of painting? – or of poetry? Or the novel? We are knee-deep in history, more than ever. We are doomed, and we cannot escape.

We could as well do without art – most of us , at least. But if we are so stubborn and do not want to be left alone with ourselves, with science, the moon, and technology; if we still percieve a sense of emptiness (still, no comfort from art); surely art-Death cannot fill such void. No more painting-for-painting’s sake. No more novel-plot-characters-novel-novel. The art which can still be a contemporary fact, which can have a reason for itself (not sentimental escapism), cannot be but a new fact. But, what news? Who can answer with general topics? Each painter, each writer, each misician will give their answer – if they can. Knowing that we need revolting against any Learning, even the most recent one; and that we need suspecting we will be chocked by our very inventions. Puliti tries to give such answers. By ardently trying to reveal one of man’s most natural, ancient, boring, ardent, and splendid needs, eros, as his starting point, Puliti chose no ancient path. No passion, no drama, no psychoanalytical clarity nor ambiuity. He was just allusive. He tried to present us with erotic ideograms where eros gets gloomier the more rational it gets, eventually reaching back to its mystery.

Puliti’s answer is clear, honest, subtle, even disquieting.

Galleries

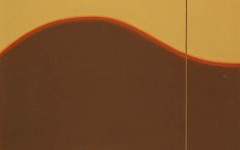

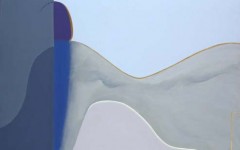

Some galleries of his most significant works

All pictures are by Federico Neri

Multimedia

Meeting held in summer 1975 at the Art Gallery of La Vecchia Farmacia of Paolo Marini, in Forte dei Marmi, during the exhibition inspired by the work of Arturo Puliti “Su Fondamenti Invisibili” by Mario Luzi.

Recording made by Emilio Tarabella. (in italian)

Contacts

For further information please use the contact form below

Cookie Policy

Cookies policy following Art. 13 Privacy Code

We inform you as follows about the use of cookies on this website.

Definition of “cookies”.

Cookies are small text files sent from the site to the computer of the person (usually the browser), where they are stored before being forwarded to the site on the next visit by the same user. A cookie can not retrieve any other data from your hard drive or pass on computer viruses or capture email addresses. Each cookie is unique for the web browser of the client. Some of the functions of cookies may be delegated to other technologies. Using the term ‘cookies’ we refer to cookies and all similar technologies.

The website www.arturopuliti.it only uses third party technical cookies.

Purposes of the processing and purposes of technical cookies

The cookies used on the website are intended to perform computer authentication or monitoring sessions and storing technical information about users accessing the server. Some operations on the Site may not be carried out without the use of cookies, that in such cases are therefore technically necessary. For example, access to restricted areas of the Site and the activities that can be carried out there would be much more difficult to perform and less secure without the presence of cookies that can identify the user and maintain the identification during the current session.

Accordingly to Article 122, paragraph 1, of the Privacy Code (after the entry into force of d.lgs.69 / 2012) “technical cookies” can be used even in the absence of consent. Incidentally, the same European board bringing together all the Authorities for the privacy of the various Member States (the so-called “Article 29″ Group) made clear in Opinion 4/2012 (WP194) entitled “Exemption from the consent to the use cookies” that cookies for which it is not necessary to acquire the prior informed consent of the user are as follows:

- Cookies with data compiled by the user (session ID), the duration of a session or persistent cookies, limited to certain hours in some cases;

– Cookies for authentication, used for the purposes of authenticated services, limited to a single session;

– Security user-centered cookies, used to detect abuses of authentication, for a persistent but limited duration;

– Session cookies for media players, such as cookies for Flash readers, limited to a single session;

– Session cookies for load balancing, limited to a single session;

Persistent cookies to customize the user interface, limited to a single session (or few ones);

Cookies for content sharing through third parties social plugins, reserved to members of a social network who have logged on.

Arturo Puliti informs therefore firstly that on the www.arturopuliti.it website are operating only technical and Third Party cookies (Google Analytics Cookies and browsers used for navigation).

Opt-out (denial of consent) regarding cookies used on the website.

The cookies used to statistically analyze accesses / site visits, the so-called “analytics”, have exclusively statistical purposes (and not profiling or marketing) and collect aggregate information not allowing the identification of the individual user. In these cases, since the current legislation requires simple and adequate instructions to be provided for opposing to analytics cookies (opt-out) and to avoid thier installation (including any mechanisms of anonymizing cookies themselves), we specify that you can proceed with the deactivation of Google Analytics as follows: open the browser, select the setup menu, click on internet options, open the tab for the privacy and choose the desired level of blocking cookies. If you wish to delete the cookies already stored in memory, simply open the tab security and delete the history by checking the box “delete cookies”.

To deepen the deactivation of Google Analytics

To delete cookies for each browser, please refer to the relevant guides on the subject:

Privacy

Notice pursuant to Legislative Decree no. 196/2003

Arturo Puliti is the Data Controller for processing of the personal data you provide to us, pursuant to article 13 of Legislative Decree no. 196 of 30 June 2003 (Privacy Act).

Data processing means collecting, recording, organising, storing, elaborating, modifying, selecting, extracting, comparing, using, linking, blocking, communicating, diffusing, cancelling and destroying data records or any combination of two or more of such operations.

Arturo Puliti will process data for the purpose of implementing the service, or one or more operations, you have requested.

Electronic instruments will be used to record, manage and transmit data in accordance with the provisions of article 11 of Legislative Decree no. 196 of 30 June 2003 to guarantee your rights, fundamental freedoms and dignity with particular reference to confidentiality and personal identity.

The personal data you provide may become known to the employees who handle data processing; data may also be communicated to external collaborators and, in general, to all parties who need access to such data in order to fulfil the requirements of the service you have requested. We are committed to not diffusing any information about single users for commercial purposes.

The data to which this notice refers is conferred strictly for the purpose of providing the service you have requested, so failure to grant consent will make it impossible to provide the service concerned.

To provide a complete service, our web site includes links to other sites some of which may be managed directly by us, by associated organisations and companies, or by others not associated with us. We are not responsible for the contents or respect of privacy provisions in relation to sites of reference that we do not manage. It is possible to identify the IP address of users who access our site.

Personal data may be transferred to countries inside and outside of the European Union in relation to execution of the service you have requested.

You are entitled to exercise the rights as set out in article 7 (Access to personal data and other rights) of Legislative Decree no. 196 of 30 June 2003, the text of which follows below.

You may request more information about processing and communication of your personal data by writing to XXXXX.

Article 7 of Legislative Decree no. 196 of 30 June 2003 – Access to personal data and other rights

I – The party is entitled to obtain confirmation of the existence or not of personal data concerning it, even if not yet recorded, and communication of such data in comprehensible format.

II – The party is entitled to obtain indication of the:

a) origin of personal data;

b) purposes and procedures of data processing;

c) application logic in the case of electronic data processing;

d) identification data of the data owner, processing executives and the designated representative pursuant to article 5, paragraph 2;

e) parties or categories of parties to which personal data may be communicated or who may become acquainted with personal data as designated representatives in national territory, processing executives or employees.

III – The party is entitled to obtain:

a) updating, correction and, in its own interest, integration of its personal data;

b) cancellation, transformation into anonymous format, or blocking of data processed in violation of the law, including processed data which need not be stored in relation to the purposes for which the data was originally collected or subsequently processed;

c) attestation that the operations described in points a) and b) were made known, in relation to their content, to the parties to which data was communicated or diffused, except when fulfilling this requirement would involve the use of manifestly disproportionate means with respect to the rights protected by the operation itself.

IV – The party is entitled to partially or totally oppose:

a) processing of its personal data for legitimate reasons even if such processing is pertinent to the purposes of its collection;

b) processing of its personal data for the purposes of advertising, direct sales, market surveys or commercial communications.

Contact us for more information.